123b | Trang chủ đăng ký 123b.com khuyến mãi 100k

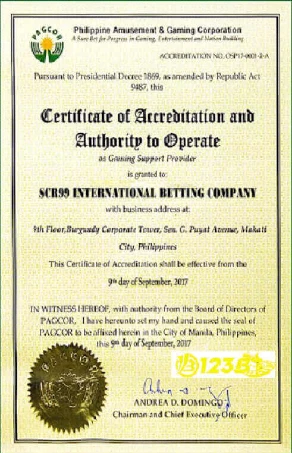

123B được biết đến như một lão đại trong giới cờ bạc Đông Nam Á. Nhà cái luôn nhận được nhiều sự tin tưởng từ quý khách hàng, nên chúng tôi cũng cố gắng đáp ứng và phục vụ khách một cách tốt nhất.

Để tri ân cũng như thu hút thêm người chơi mới, 123B tung ra siêu nhiều gói quà ưu đãi khuyến mãi hấp dẫn như:

- Thưởng nạp lần đầu lên đến 28.789.888 đồng khi đăng ký tài khoản mới.

- Thưởng nạp lần hai lên đến 16.789.888 đồng chỉ cần 1 vòng cươc.

- Điểm danh mỗi ngày nhận ngay 588.888 đồng, đạt mốc được gửi tiền ngay lập tức.

- Sinh nhật người chơi tặng thưởng miễn phí lên tới 28.888.888 đồng.

- Giới thiệu người tham gia nhận quà miễn phí không giới hạn mỗi ngày.

Để nhận khuyến mãi trên thì mời quý hội viên hãy truy cập ngay trang websie https://jiddu-krishnamurti.net/ chính thức tại 123b để nhận ngay những phần thưởng hấp dẫn và trải nghiệm trò chơi mới nhất cùng nhà cái chúng tôi.

👉 Top nhà cái uy tín đã có duyên hợp tác cùng 123b

⚡️Nạp lần đầu tặng 100% giá trị lần nạp đầu ⚡️Hoàn cược thể thao, casino 100% không giới hạn

⚡️Thưởng 3 triệu lần đầu cược chơi casino, thể thao ⚡️Hoàn trả bắn cá, quay hũ lên tới 2.5%